Introduction

One of the key duties faced by all Compliance Officers for Legal Practice (COLPs) and Compliance Officers for Finance and Administration (COFAs) is the need to make a prompt report to the SRA as to “any facts or matters that you reasonably believe are capable of amounting to a serious breach of the terms and conditions of your firm’s authorisation, or the SRA’s regulatory arrangements which apply to your firm, managers or employees” (paragraph 9.1(d) and 9.2(b) of the SRA Code of Conduct for Firms).

This requirement first arose in sections 91 and 92 of the Legal Services Act 2007 and was first incorporated into the rules in the form of the “material breach”, transforming into the “serious breach” with the introduction of the 2019 Standards and Regulations.

It is a fact of life in practice today that the majority of firms could easily find themselves subject to a breach of the SRA’s regulatory arrangements. Some breaches are so minor that provided they are rectified immediately, no harm is done. Others, however, may be a little more critical. Whether the breach be from a slip up with client account, inadvertently breaching confidentiality, not following the Transparency Rules to the letter or failing to advise a client as to all aspects of costs, breaches occur in the best run of firms. How you deal with those breaches, and the follow up that you put in place, is what can make the difference between serious consequences and a slap on the wrist.

Only breaches that are deemed to be “serious” need to be reported to the SRA. There continues to be a duty for you to “keep and maintain records to demonstrate compliance with your obligations under the SRA’s regulatory arrangements”, which implies the need to keep records of all potential breaches, however it is only the serious breaches that need to be reported.

What is a Serious Breach?

That of course begs the question as to what amounts to a serious breach.

As was the case previously with material breaches, there is little to be found in terms of guidance from the SRA as to what constitutes a “serious” breach for the purposes pf paragraph 9.1(d) or 9.2(b) of the Code of Conduct for Firms. It is not defined in the Glossary to the Standards and Regulations. This is not withstanding that there is also a duty upon all solicitors to “report promptly to the SRA or another approved regulator, as appropriate, any facts or matters that you reasonably believe are capable of amounting to a serious breach of their regulatory arrangements by any person regulated by them (including you)”.

To find out what constitutes a serious breach, a little detective work is required.

Note (x) to Rule 8 of the Authorisation Rules 2011 did provide some guidance as to what constituted a material breach and this is still useful in determining what might amount to a serious breach. This provided that:

“In considering whether a failure is “material” [or “serious” in current rule terminology], the COLP or COFA, as appropriate, will need to take account of various factors, such as:

- the detriment, or risk of detriment, to clients;

- the extent of any risk of loss of confidence in the firm or in the provision of legal services;

- the scale of the issue; and

- the overall impact on the firm, its clients and third parties”.

Thi is not necessarily that helpful a definition in practice and is further complicated by the fact that a material breach could be a breach which, on its own, would not have been material, but which might become material if it forms part of a series of breaches.

The Law Society, in guidance since updated, commented at the time that “Compliance officers must remember that the SRA Code covers a wide range of issues including business management and financial stability and notify the SRA if they believe the practice is in serious financial difficulty” whilst in their practice advice FAQs from around the same time they stated:

“What is ‘material’ will depend on the firm and the circumstances around possible failures to comply with the SRA Authorisation Rules, and the SRA will judge each case on its own merits. As set out above, factors such as the detriment or risk of detriment to clients, the scale of the issue and overall impact on the firm will need to be considered in deciding whether a failure is ‘material’.”

Is there any SRA help on a definition?

Fortunately, however, there is some guidance to be had.

This is to be found in the SRA Enforcement Strategy (not part of the Standards and Regulations). The Strategy provides information on the reporting of concerns at paragraph 1.2. where it states that:

“Reporting behaviour that presents a risk to clients, the public or the wider public interest, goes to the core of the professional principles of trust and integrity. It is important that solicitors and firms let us know about serious concerns promptly, where this may result in us taking regulatory action. We do not want to receive reports or allegations that are without merit, frivolous or of breaches that are minor or technical in nature – that is not in anyone’s interest. We do want to receive reports where it is possible that a serious breach of our standards or requirements has occurred and where we may wish to take regulatory action”.

The Strategy goes on to set out when a report should be made. In a nutshell this is:

“where a serious breach is indicated, we are keen for firms to engage with us at an early stage in their internal investigative process and to keep us updated on progress and outcomes. And, we may nonetheless wish to investigate the matter, or an aspect of a matter, ourselves – for example because our focus is different, or because we need to gather evidence from elsewhere”.

It also sets out who should make the report, where the preference is for reports to be made through the firm’s compliance officer so as to avoid “multiple or duplicate reports being made” and so as to allow “compliance officers to use their expertise to make professional judgments in light of the facts (and following investigation, where appropriate)”.

The assessment as to seriousness that the SRA will make involves a number of factors including past conduct and behaviour and mitigating factors such as a low likelihood of future risk or repetition of the behaviour. The key factors that the SRA will take into account include:

- the nature of the allegation – certain types of allegations are regarded as inherently more serious than others, for example, allegations of abuse of trust, taking unfair advantage of clients or others, the misuse of client money, sexual and violent misconduct, dishonesty, criminal behaviour, discrimination and harassment.

- intent and motivation – for example people who are trying to do the right thing and those who are not. The SRA acknowledge that both human and system error is inevitable and no action will normally be taken where a poor outcome is solely the result of a genuine mistake unless the failure to meet SRA standards or requirements arises from a lack of knowledge which the individual should or could reasonably be expected to have acquired, or which demonstrates a lack of judgment which is of concern. Factors such as the experience and seniority of the individual involved (in other words, whether they knew, or should have known, better) will be taken into account.

- harm and impact – a further factor is the harm caused by the individual or firm’s actions and the impact this has had on the victim. This will be fact sensitive and depend on individual circumstances. Also germane will be the numbers of victims, the level of any financial loss or any physical or mental harm.

- vulnerability – some clients are more susceptible to harm so the onus upon the firm or individual will be correspondingly higher. It is felt that there is a need to protect those who are less able to protect themselves and an allegation will be seen as being particularly serious where vulnerability is relevant to the culpable behaviour.

- role, experience and seniority – higher levels of responsibility will be expected of those who are more senior and experienced and who should have higher levels of insight, foresight, more knowledge and better judgment.

- regulatory history and patterns of behaviour – does the behaviour form part of a pattern or repeated misconduct?

- remediation – has remedial action been taken?

Do bear in mind, however, that these are the factors that are applied after a matter has been reported or come to light. It is the job of the COLP or COFA (as relevant) to interpret these and apply them to the breach in question. Thus, if it is likely that the SRA will take a serious view of the breach, then it is reportable whereas if the breach is minor, unlikely to be repeated and with negligible effect on clients or their interests, then it may not need to be.

Applying criteria in practice

Firms wishing to apply some degree of uniformity to the process of whether or not a breach is serious may like to think ahead as to the types of issues that might give rise to a report and those that will not. This will have the added benefit that steps may be able to be taken in order to prevent or ameliorate the effects of such a breach – which if nothing else will place the firm in a better position with the SRA.

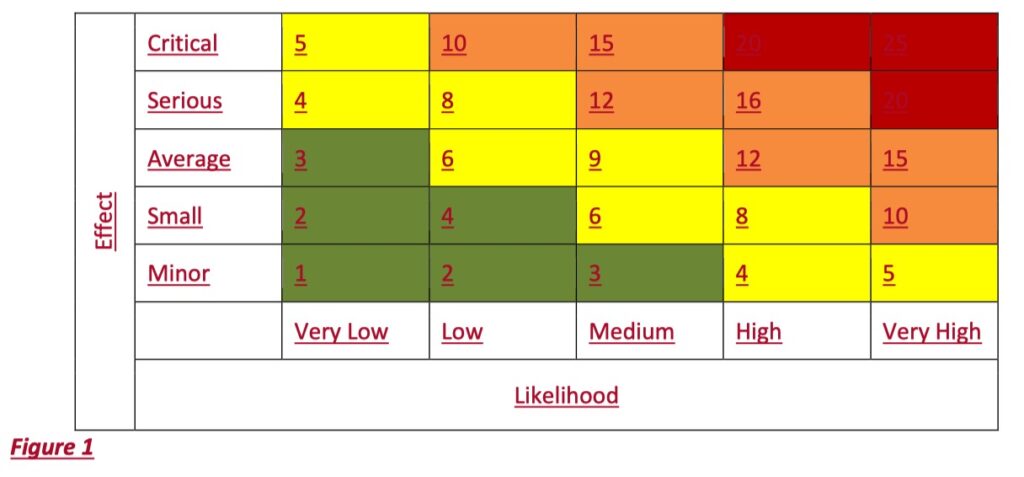

The process might be assisted by the use of a risk grid where the firm can plot the likelihood of the breach arising or being repeated or whether there is any element of dishonesty or intent on the part of the person committing the breach against the effect the breach will have, or is likely to have, on clients, their interests, the firm, the reputation of the profession, etc.

For each breach you give a figure from 1 to 5 as to the likelihood of the breach occurring or being repeated/the culpability of the person concerned against the extent of the impact that breach would be likely to have, were it to occur. Breaches that are unlikely to re-occur, have been committed without intent or blame and will have little effect need to be given less prominence in terms of prevention than breaches that are either more likely to happen again, are as a result of dishonesty or, were they to occur, likely to have damaging consequences for clients, the firm, the profession, and so forth. See figure 1.

When looking at putting in place processes to avoid those breaches, high-risk potential breaches need to have robust solutions put in place to prevent them from occurring. Low risk breaches need to be given lesser prominence. The closer to the top right hand corner of the grid, the more important it is that the firm take preventative steps where possible.

When looking at putting in place processes to avoid those breaches, high-risk potential breaches need to have robust solutions put in place to prevent them from occurring. Low risk breaches need to be given lesser prominence. The closer to the top right hand corner of the grid, the more important it is that the firm take preventative steps where possible.

Bear in mind that the aim is to have a manageable plan for preventing breaches that is not so complex or time-consuming as to damage the ability of the firm to function.

What Constitutes a Serious Breach?

As already pointed out, there is very little guidance from the SRA as to what in practice constitutes a serious breach and with legal practice being as complex as it is, it would be almost impossible to provide a definitive list of the types of situation that should be reported. Bear in mind that often the circumstances of a breach can be as important as the nature of the breach itself. Thus, a minor breach that occurs regularly because of a systemic failure on the part of the firm may need to be reported (together with the firm’s plans for addressing the issue going forward) whereas that same breach that occurs as a one-off and is unlikely to occur again may not need to be.

Purely as an aide to making your own decision, the following are examples of what could constitute a serious breach. As said earlier, do not assume that this is an exhaustive list or that the absence from this list means that you do not need to make a report. They include:

- violence,

- sexual misconduct,

- other criminal behaviour,

- dishonesty,

- taking unfair advantage, in particular in relation to vulnerable clients,

- misuse of client money,

- abuse of trust,

- covering up or lying about a less serious breach,

- breach of confidentiality including the loss of papers and files or sending the wrong information to the wrong person,

- knowingly acting in a conflict situation,

- selling to, lending to, buying from or borrowing from a client without that client having obtained independent legal advice;

- using a power of attorney to gain a personal advantage,

- repeated failure to notify client of necessary information,

- accepting referrals in breach of the provisions of LASPO,

- obtaining instructions by means of unsolicited approaches to members of the public or accepting referrals from others who have done so.

- acting for a client who proposes to make a gift of significant value to you or a member of your firm or family without requiring the client to take independent legal advice,

- ceasing to act for a client without good reason and without providing reasonable notice,

- entering into unlawful fee arrangements such as an unlawful contingency fee,

- accounts related breaches including paying client money into the wrong client account, unauthorised or fraudulent withdrawals from client account, use of client account as a banking facility, failing to keep adequate accounts and paying client money to the wrong third party,

- intentional discrimination by a member of staff against a client, third party or employee,

- harassment and bullying within the firm,

- misleading the court or knowingly allowing a client to mislead a court,

- being in contempt of court,

- serious management related issues such as on-going failure to provide adequate supervision or to monitor files or the work of junior colleagues, failure to deal adequately with complaints or breach of an undertaking.

What do I do if a serious breach occurs?

If a serious breach does occur then the firm, through the COLP or COFA, should make a report to the SRA as soon as possible. Failure to make reports promptly can also lead to further harm or loss and carries a risk that regulatory action will be taken against the firm for not giving the SRA the information that it requires in a timely manner.

For these purposes, the definition of “prompt” in terms of the report can present COLPs and COFAs with a somewhat thorny problem. The SRA currently take the view that it should be as soon as possible after the breach has been discovered. However, this does not take account of the fact that it may not be possible to make an adequate report until further investigation has taken place or until the facts are known. Perhaps the best advice is to say that it should be reported at the first opportunity to do so after it is discovered. This may mean not waiting until steps to remedy the breach have been taken or it may mean, in circumstances where remedy is more important than report, taking steps to remedy the problem first. As with so much else in this area, the circumstances will dictate when it is appropriate to do so.

Wherever possible the firm should take all reasonable steps to correct the breach – whether or not it is a serious one – and should also take steps to ensure that procedures are put in place to prevent such a breach arising in the future. Clearly this will not always be possible. Note that taking such steps may well make the SRA look more favourably on the firm.

Not all reported serious breaches will necessarily result in any action being taken by the SRA towards the firm. Again it depends upon the nature of the breach and the outcomes that arise from it.

When making the report, the factors used by the SRA in determining a breach and which are set out in the SRA Enforcement Strategy should always be borne in mind. Thus, the report should not only state the factual surrounding the breach but should also contain:

- an explanation as to why the breach occurred,

- details of why it will not occur again or the steps to be taken to prevent it from occurring again

- an outline of the steps taken to put right any detrimental result of the breach (including contact with the client),

- an expression of regret or remorse, both by the firm and where appropriate the individual,

- a statement to the effect that there is no evidence that it was a repeated breach, the result of misconduct, fraudulent or part of a pattern of actions or behaviours.

Should further steps, including disciplinary steps, be required then these should also be referred to.

It may also be beneficial to include any “mitigating circumstances” by way of an explanation as to why the breach occurred. This might include what the SRA refer to as ‘contextual’ mitigation – i.e. the events surrounding the breach – or personal mitigation such as the background, character and circumstances of the individual or firm, the relative inexperience of the individual or other personal factors.

Finally, consideration should be given in the report to other factors including:

- intent/motivation – was the breach caused by someone who was trying to do the right thing?

- harm/Impact – the harm caused by the individual or firm’s actions and the impact this has had on the victim or victims. This may include factors such as numbers of victims, the level of any financial loss or any physical or mental harm.

- vulnerability – the report should make it clear if the client was vulnerable in any way.

Bear in mind at all times that committing a breach of the rules is rarely going to produce as serious an outcome for the firm as trying to hide the breach with it then being discovered at a later stage.

Finally, the report should be in writing and may be made either to the SRA at its offices in Birmingham or to the email address report@sra.org.uk. Although there is no particular format in which a report needs to be made the SRA encourage you to make use of their reporting form which can be found at (https://www.sra.org.uk/consumers/problems/report-solicitor). In practice this form is more suited to reports from members of the public, so you would be better in most cases reporting by letter or email.